Profit-Sharing in Smaller Partnerships

In my most recent article, I looked at some alternative options for profit-sharing among law-firm partners. All of the options I described can be found in mid-sized and large firms. They can all be made to succeed and they can all be made to fail; there is no ‘best option’.

In my most recent article, I looked at some alternative options for profit-sharing among law-firm partners. All of the options I described can be found in mid-sized and large firms. They can all be made to succeed and they can all be made to fail; there is no ‘best option’.

What about small partnerships (where the majority of practising lawyers are to be found)? All of the issues around performance and sharing that pop up in large firms also exist in small firms. Furthermore they often exist in environments of greater complexity, not lesser; layers of complexity – like familial involvement; long term, perhaps even multi-generational, friendships; longer-term career progression (articled clerk to equity partner is not an unusual journey within a small law firm); equity purchase involving ‘goodwill’; and self-funding for day-to-day cash-flow needs – are but a few added complications. To date, equal sharing and suppressed (if not silent) dissatisfaction have been the default ‘easy options’.

In the past, partners currently in their 50s and 60s were, by and large, comfortable with (or at least tolerant of) equal sharing. This was basic portfolio theory in action: ‘I’ll be busy when you are not and visa-versa. If we share equally, all will be better off over time’. Theirs has been a career journey that coincided with the big shift in law firms from ‘cottage artisans’ to managed commercial businesses that occurred throughout the 1980s and continues still. During this period, hierarchies became less important and specialisation more important. Still more significant, measurement and ‘accountability’ became central to ‘good business’. ‘Performance’ emerged as a construct that applied more to the individual than the collective. Not coincidentally, theirs was also a career journey that has seen a significant increase in the financial success of law firms. Many of these partners commenced with modest income expectations, expectations that have been ratcheted up over time.

Simultaneously (in Australasia for sure and likely elsewhere), as business cycles lengthened and corporate memory shortened, portfolio theory as a risk-management tool became less significant. ‘The next downturn’ used to be five years away. Now, any lawyer in Australia under 50 years of age hasn’t practised through an economic recession. Of course, ups and downs, busy times and quiet times still happen, but younger partners seem significantly less fearful of the prospect. These partners seem to be attracted to a more immediate ‘this year’s reward for this year’s performance’ approach. Many of these younger partners started with relatively high income expectations.

There is a lot to like about equal sharing, but increasingly small partnerships are asking me about alternatives. They like the upside of equality but want the capacity to reward outlier performance. They are particularly interested in acknowledging sustained higher performance – and, increasingly, sustained higher performance among relatively young partners (highly mobile talent).

In these circumstances I usually suggest that firms set aside a proportion of the net profit (before principals’ salaries) to be used as a bonus pool. The purpose of the pool is recognition and reward. (A side note: Theoretically the prospect of reward should provide an incentive to improve, but invariably it doesn’t. My advice? If you introduce a bonus pool as a behavioural change strategy you can avoid disappointment by lowering your expectations now!)

Firms usually allocate 5 to 15 percent of total profit (collected fees less expenses) before tax to the bonus pool.

Bonus pools usually work retrospectively and annually.

I have seen a number of approaches to allocating the bonus pool:

- In firms with less than ten partners a voting method is sometimes used. All partners vote on how the bonus should be allocated. Votes are tallied and profits allocated according to the ‘score’. Firms often publish criteria to be assessed but, in my experience most partners and directors concentrate on fees controlled. Interestingly, managing partners usually finish in the middle of the pack, never at the top.

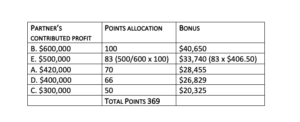

- In firms where the data is available, the bonus pool may be allocated on the basis of profit contributed. A partner’s contributed profit is determined by totalling their fees personally billed with those billed by their direct reports and those introduced or referred to other groups, less the direct salary cost. In the case of referred fees this requires determining an hourly direct cost of each billable hour. This produces an index that will always be greater than the firm’s actual profit because there is a necessary double count of referred work, with both referrer and referee receiving credit. The partner with the most contributed gross profit is allocated 100 points and the remaining partners are pro rated according to their contributed profit. The total points are summed and a value determined for each point. The bonus is then distributed on the basis of points multiplied by the per point value. For example (see Table, below), assuming we set aside a bonus pool of $150,000, and we have five partners with contributed annual profit. Pro-rata contribution points total 369, therefore each point is worth $406.50.

- Because the calculation of contributed profit is often cumbersome and frequently negotiable, some firms use total fees controlled to allocate bonuses. Some use data only from the current year, others use a three-year weighted average. In the case of a weighted average, the most immediate year is weighted by a factor of 3, last year by a factor of 2 and the year before last by a factor of 1. This has the effect of rewarding partners with a growing practice relative to those with a declining practice. This method also uses the above weighting methodology and is usually less controversial than the ‘profit contributed’ method, although often misleading. A partner with a number of highly paid senior staff will most likely do well under a fees-controlled methodology. To do well under a profit-contribution model, partners need lower cost leverage.

- I have seen bonus pools allocated using a ‘balanced performance’ approach. Partners are assessed for financial contribution, citizenship (basically, not being toxic), and practice-building efforts. Although theoretically ideal, this requires an assessment process much of which is subjective. Partner-performance-management programmes don’t always work well in small firms (it can be a bit like uprooting a pot plant to check on the health of the root system; sometimes it’s best to leave them be, especially if you are all good friends or family).

- In some firms the managing partner recommends allocations. These recommendations are usually accepted. This method requires trust and transparency. Gen X partners and the few millennial partners I’ve met hate it.

Of course, any of the systems that I outlined in my last article could also be made to work in small firms. I do however want to wave one warning flag: differential profit-sharing (i.e., anything other than equality) consumes valuable partner time and in extreme cases gives rise to bureaucracy. Small firms can afford neither.

If unequal sharing is to work in a small partnership, in my experience the methodology needs to be transparent, understood by all partners, meaningful (not token) and, above all, trusted.

Dr. Neil Oakes has served the Australasian legal profession since 1989. Neil lives on the mid-north coast of NSW near the small coastal town of Scott’s Head and enjoys all of the pleasures of coastal life. He has a large garden in which he tries to grow vegetables organically, battling every bug in Christendom. His interests include art, cooking, eating and the odd glass of wine.